A Smaller Footprint

is One Step Further

IDH leads a working group with key aquaculture players to quantify and minimize their carbon footprint.

Pamela Nath, Sally Tabares, and Lisa van Wageningen

July 17th, 2023

Since the Industrial Revolution, human activity has significantly increased the concentration of greenhouse gases (GHGs) in the atmosphere at an alarming rate.

What once served as a natural component to retain heat from the sun on Earth, preventing temperatures from plummeting at night, has now become a threat to the sustainability of our planet.

The World Meteorological Organization has announced that since that time, the accumulation of carbon dioxide has increased by 149%, methane by 262%, and nitrous oxide by 124%.

As a consequence, global warming has skyrocketed. The rise in temperature, melting glaciers, and recurring extreme weather events are just some of the most evident effects of climate change. However, as this list progresses, it becomes imperative to question whether we can truly ignore the contribution of the aquaculture industry to the events we are currently facing.

According to the study “Reducing food’s environmental impacts through producers and consumers” by Joseph Poore and Tomas Nemececk, within the total global greenhouse gas emissions, 26% can be attributed to food systems. This includes emissions from land-use change, deforestation, water body alteration, agricultural production, processing, transportation, packaging, and product sales.

26% of global greenhouse gas emissions come from food systems.

Globally, in 2019, seafood provided approximately 17% of animal-based protein and 7% of total protein, according to the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations.

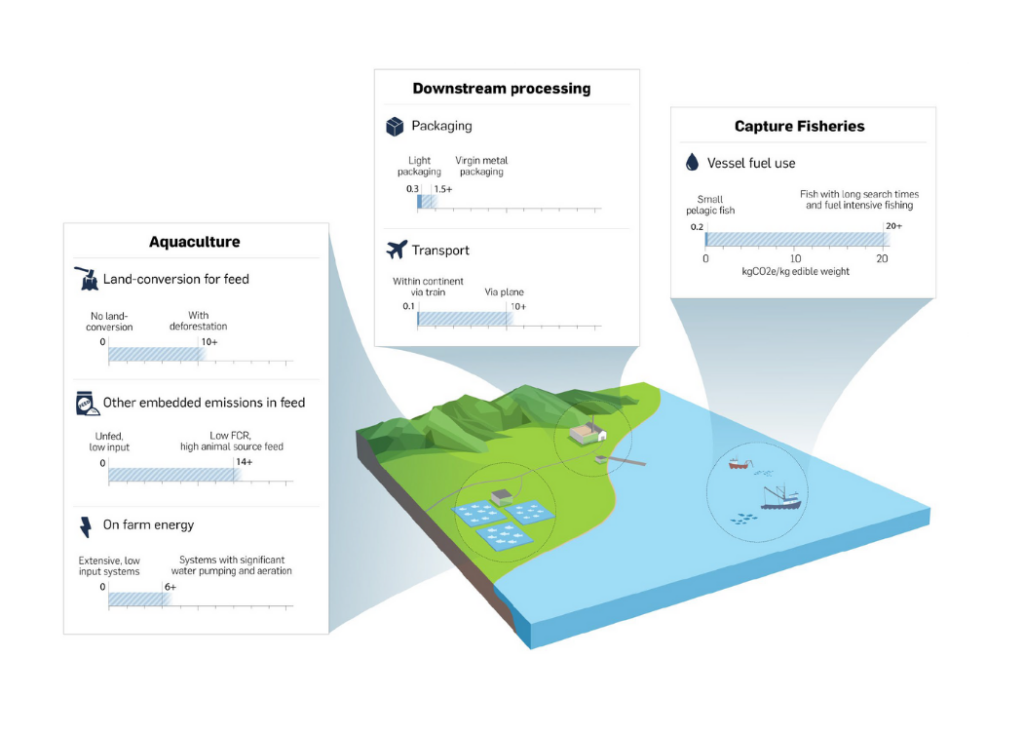

Where do the GHG emissions from seafood come from?

Source: Setting Science-Based Targets in the Seafood Sector: Best Practices to Date

By 2030, it is projected that the production of seafood will increase by 13% compared to 2022, and approximately 59% of the seafood available for human consumption will come from aquaculture, according to estimates by the FAO.

Given that aquaculture is among the fastest-growing sectors in the global food industry, it is urgent and necessary to reflect on its impact on the planet.

Currently, the environmental impact of aquaculture throughout its lifecycle is not well understood. There is a lack of information regarding the environmental footprint of aquaculture across its entire value chain.

For this reason, it is crucial to understand this measurement in terms of water usage, water quality, biodiversity, fossil fuel consumption, plastic usage, among others, in order to determine the carbon footprint they generate. The carbon footprint is defined as the amount of greenhouse gases emitted directly or indirectly as a result of specific activities in the sector.

The lack of this knowledge has prompted the Sustainable Trade Initiative (IDH) to launch and lead the Aquaculture Working Group on Environmental Footprint, a coalition of organizations aiming to assess the negative impact of products involved in the aquaculture production process in order to differentiate between those with better environmental performance and those in need of improvement.

Aquaculture Working Group on Environmental Footprint

Its main objective is to understand, measure, and reduce the environmental footprint of aquaculture throughout the entire supply chain.

Footprint measurement allows quantifying the environmental impact throughout a product’s life cycle. To perform these calculations, the framework of Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) is followed, which enables understanding the complete life cycle footprint of a product, taking into account all stages of production.

By integrating all stages, this assessment helps to observe the interactions between these stages and identify hotspots or areas in the supply chain with the highest environmental impact. “Understanding which part of the production process is critical in GHG emissions allows companies to create solutions to reduce the footprint of aquaculture where necessary,” says Lisa van Wageningen, Aquaculture Program Officer at IDH.

Furthermore, by quantifying this impact in numbers, it becomes easier to compare the sustainability of one product with another. However, Van Wageningen highlights the importance of alignment among companies and certification schemes to measure product performance using the same methodology, ensuring true comparability. This way, the time and money spent on collecting data in different formats can be invested in improving the situation and causing less harm to the environment.

One of the goals of the Working Group is to reach a situation where producers with good practices are rewarded and where there is an incentive for those who do not implement them to improve.

“If each company independently decides which methodology to use, we run the risk of comparing apples to pears. For example, if one company only measures the environmental impacts of one kilogram of shrimp at the farm level and then compares it to the environmental impact of one kilogram of shrimp from another company from its origin to retail, they are comparing two completely different figures while making claims about the sustainability of their product,” explains Van Wageningen.

For this reason, the Aquaculture Working Group provides a system that enables alignment among suppliers to measure products in the same way, facilitating comparisons with other supply chains, aquaculture products, and proteins.

Here, IDH and ISEAL Alliance convene certification programs that verify the collection of data on the environmental footprint, ensure that these calculations are conducted under the same standards, and enable companies to make substantiated claims about what they produce.

Thanks to this system, the Working Group also assists its members in fulfilling other objectives, such as the requirements of the Science Based Targets initiative (SBTi) for scope 3 emissions. SBTi provides science-based targets that organizations set to effectively reduce their greenhouse gas emissions.

On the other hand, scope 3 emissions refer to the emissions derived from the companies an organization purchases from or sells to, which are part of the supply chain but are not directly under the organization’s control.

The Working Group contributes to this goal because in order to measure a company’s scope 3 emissions, companies must gather information about the environmental footprint of the products that the Working Group already collects as part of the project.

Another characteristic of the Working Group is that its members work in a precompetitive and cooperative manner to prioritize issues, initiate projects, create metrics and methodologies, and learn together.

By working together, companies can develop, test, and scale solutions that they couldn’t achieve on their own. In fact, within the group, a tool for measuring environmental footprint has been developed, which participants have used to assess products such as shrimp, tilapia, pangasius, and salmon, ensuring consistent results and simplifying the process of quantifying the footprint.

“Each actor in the supply chain can influence the environmental footprint of a product. So, to achieve changes, it is necessary for all actors in the chain to work together, ” expresses Van Wageningen.

For this reason, the Working Group is composed of 17 participants from different areas, including retailers, traders, producers, animal feed companies, technology providers, and NGOs. Among the project members are Tesco, Marks & Spencer, Hilton Seafoods, Regal Springs, Seafresh Group, Global Salmon Initiative, Nordic Seafood, Sustainable Shrimp Partnership (SSP), among others.

SSP has been part of this initiative since its inception, with the aim of understanding the environmental footprint of the shrimp aquaculture industry and specifically its product.

“We have the task of identifying the new challenges and opportunities to implement improvements within the shrimp sector. What we consider sustainable today may not be sufficient in five years,” comments SSP Director Pamela Nath. “Being aware of the impact we are generating allows us to identify which issues to address and which are the critical points that need intervention in order to achieve even better performance.”

Nath explains that the Working Group allows SSP to be in contact with other industries and actors from different stages of the value chain. Therefore, it is easier to share experiences and learn from what others are doing in their respective areas of work.

The skills acquired and improvements achieved act as a blueprint for other industries to follow. Moreover, she highlights that a notable aspect of this project is its comprehensive approach, which not only focuses on measurement but also encourages participants to set short, medium, and long-term goals based on identified areas of concern. These goals are gradually accomplished as the program advances.

“At SSP, we see ourselves as an innovation laboratory, constantly striving to stay ahead and lead the way towards sustainability. Engaging in projects like this enables us to showcase tangible improvements through practical examples. By doing so, we inspire others to enhance their practices or become part of our group,” Nath adds.

After conducting pilot plans with some of its members, the Working Group has confirmed and identified several critical points in the industries, which can vary from one production system to another. Therefore, it is important for each company to understand its own operations and supply chain. Among the identified hotspots, the following stand out:

The Working Group has already identified critical hotspots within the industry

1Ingredients used in aquaculture feed, such as soy, which can significantly contribute to the overall environmental impact in aquaculture.

2Land-use change, such as deforestation for converting it into agricultural land, which can represent a significant percentage of the environmental footprint of food, particularly in terms of greenhouse gas emissions.

3Sourcing of raw materials for feed ingredients, which can have notable differences in water footprint between supply chains, depending on whether the ingredient has been cultivated with irrigation or not.

4Energy derived from the burning of fossil fuels, which can significantly contribute to the carbon footprint in cultivation and processing stages.

5The use or loss of refrigerant gas throughout the supply chain can be a significant source of greenhouse gas emissions.

Land-use change is one of the critical points that greatly affects the environment, as it influences both greenhouse gas emissions and biodiversity. Throughout their lifespan, trees absorb CO2 from the atmosphere through photosynthesis and use it to produce carbohydrates and other organic compounds. However, when trees are cut down, the carbon stored in their biomass is released into the atmosphere because they are no longer alive to maintain and utilize that carbon in their structure. Additionally, animals, plants, and genes lose their habitat when the forest is lost.

A distinction can be made between land-use change for feed ingredients and land-use change for aquaculture production farms. If the land previously hosted a forest or wetland and is converted to aquaculture or inputs for aquaculture food production, that loss is accounted for in the environmental footprint of the product.

Another decisive hotspot for the environmental footprint of aquaculture is feed. The Blue Food Assessment project shows that feeds impact the environment both in their production, due to the environmental impact of their ingredients, and in the amount of feed used in aquaculture farms, which often results in direct emissions to ponds when not fully consumed.

“Food should be addressed at all levels, both in aquaculture farms and in food production,” announces Van Wageningen. “Feed companies want to make changes and have set goals to reduce the footprint of their feeds. They also want to understand the impact of their feeds on the farm. We believe that the best approach is to collaborate for improvement, rather than simply switching from one feed ingredient to another or from one supplier to another. Giving people the opportunity to progress and supporting them in those reforms.”

The Working Group considers the possibility that aquaculture and agriculture products can have a positive impact on the environment if produced sustainably.

Developing a product that emits more greenhouse gases than necessary, pollutes water, and negatively affects biodiversity is counterproductive. The industry needs to make progress in these areas because climate change affects its business operations.

Droughts, extreme weather events, and salinization are significant risks that the industry faces. Therefore, it is essential to consider the impact of aquaculture on the environment and adopt sustainable measures to mitigate climate change.

The most important step is to identify the key hotspots along the supply chain, as the measures to reduce them will depend on the primary environmental impacts generated by a product.

Aquaculture, along with other industries, can significantly contribute to this challenge, but only through effective collaboration can we ensure a healthy future for the planet.